In 1837, the poet Robert Southey published a collection of essays called The Doctor. Even though he was the British Poet Laureate, and a contemporary of Wordsworth and Coleridge, this little collection contained something that would outlast all of his other works. It was called “The Story of the Three Bears,” and it was the first printed version of Goldilocks.

All of the elements were there—the three bears with their porridge, chairs and beds, the building repetition that delights every little child who hears it. But there is one, curious thing—in this version, the intruder was not a golden-haired little girl, but an old woman.

In a way, it makes more sense. Most children, if they broke into a strange house, would probably not spend most of their time looking for a nice place to rest, no matter how filling the porridge. And yet by common consent, as the story started to be retold, the little girl took over.

Because there are some stories that suit a child protagonist. This is more than just appealing to a similarly young audience—after all, for a children’s book to endure it must captivate parents as well. A child protagonist has less “baggage” than an adult. We might well ask what Southey’s old lady thought she was doing creeping into a strange house, but we would never need to ask the same of Goldilocks—she was simply curious, and had little respect for property.

Yet that doesn’t mean that child protagonists are harmless, any more than real children. J.M. Barrie, in Peter Pan, knew very well that innocence is not at all the same as kindness:

“Who is Captain Hook?” [Peter] asked with interest.

“Don’t you remember?” [Wendy] asked, amazed, “how you killed him and saved all our lives?”

“I forget them after I kill them” he replied carelessly.

Of course, Peter is an unusual case, because he is not able to grow up, not allowed to develop the sense that anything is more important than his eternal playtime. This is important, because the prospect of aging, of trading innocence for experience, is present in almost every children’s story. It might be very central, like in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials, where the whole plot hinges around the moment where Will and Lyra move from childish fluidity to more adult knowledge, but this is not necessary. Even in Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, Max chooses to leave his wild otherworld, where he is an all-powerful king, to return to the safety and comfort of home. He recognizes that he is not yet ready for independence.

But in most stories where the main character is a little older than Max, independence is exactly what is needed. No-one can have a story truly their own if a responsible adult will come and sort everything out for them. Parents are rarely permitted to get involved. They don’t necessarily need to be eaten by a crazed rhinoceros (Roald Dahl’s distinctive method from James and the Giant Peach), but the child must be allowed to overcome their own obstacles. The parents must be absent, incapacitated or, occasionally, given their own plot. Brian Jacques, in his third Redwall book, Mattimeo, achieves a very rare balance by having half the story revolve around the eponymous young mouse, captured by slavers, and half around his father, the warrior Matthias, who is searching for him. Both of them learn from the experience. But then again, Matthias had first been established as a young protagonist himself, in the original book, Redwall. In a way, he is still coming to terms with becoming part of a protective older generation, rather than the young adventurer.

Because this tension between roles is at the heart of the child protagonist. They must forge a path between the opposing forces of comforting adult protection and an independent, personal existence.

This is dependent as much on culture as age. Juliet, of Romeo and Juliet is thirteen, yet is not a child protagonist because it was not uncommon to marry at that age in that era. A similar story nowadays, with the ages unchanged, would almost certainly question Romeo’s motives. In contrast, the shock of John Wyndham’s Chocky relies entirely on the shift from the main child character—Matthew—apparently talking to an ordinary imaginary friend, to the realization that he is possessed by an alien intelligence. Notably, the telling moment, early on, comes when Matthew is found arguing with “Chocky” over whether there should be seven or eight days in a week. But as his father says: “to an eleven-year-old a week is a week and it has seven days—it’s an unquestionable provision, it is just so.” This kind of discussion is entirely outside of Matthew’s usual way of thought—he has become involved in something far larger, something which terrifies his parents. In contrast, all that terrifies Juliet’s parents is that their daughter might not marry their chosen suitor—she is entirely part of the adult world.

Which leads us back to Goldilocks—the fairy tale heroine. She is neither too childish and protected, her parents are apparently quite happy to let her roam around the bears’ neighborhood. Nor is she too independent—she obviously has no trouble with regarding all food and furniture as being provided for her, and she is never in any real danger.

No, Goldilocks possesses the ideal combination for a child protagonist—the inventiveness and curiosity of an independent mind, unhampered by the dreary worries of adulthood. Or, as she would say, she is “just right.”

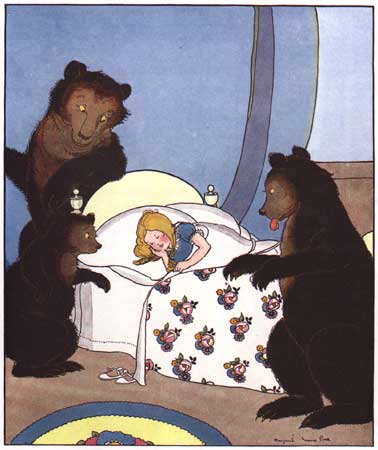

* Image is from this website, crediting Margaret Evans Price. Full citation: Wadsworth, Wallace C. The Real Story Book. Margaret Evans Price, illustrator. Chicago: Rand McNally & Company, 1927.

David Whitley is British, and a recent graduate of the University of Oxford. His first novel is The Midnight Charter, a fantasy adventure for young adults which, to his complete astonishment, has sold on five continents in thirteen languages. The first of a trilogy, it will be published in the US by Roaring Brook in September.